|

The Journal of Food Technology in Africa

Innovative Institutional Communications

ISSN: 1028-6098

Vol. 9, Num. 1, 2004, pp. 17-22

|

The Journal of Food Technology in Africa Vol. 9 No. 1, 2004, pp. 17-22

Drying Kinetics, Physico-chemical and Nutritional Characteristics

of "Kindimu",

a Fermented Milk-Based-Sorghum-Flour

*Tatsadjieu N.L.1, Etoa F-X2, Mbofung C.M.F.1

1University of Ngaoundere, School of Agro-Industrial Sciences,

Department

of Food Sciences and Nutrition, Ngaoundere - Cameroon. P.O Box 454.

2University of Yaounde, Faculty of Science, Department of Biochemistry,

Yaounde - Cameroon. P.O Box 812.

*Corresponding author

Code Number: ft04003

ABSTRACT

"Kindimu", a fermented milk-based cereal foods made by sun drying a mixture

of fermented milk and cereal

flour is a common flour ingredient in the central African region. A study was

carried out to evaluate the

effect of processing methods on the drying behaviour, functional and nutritional

quality of such a food

prepared from sorghum flour and fermented milk. A mixture of 1 part sorghum

flour (germinated or non -

germinated) and the 2 part (w/w) on fermented milk was coated on aluminium

trays to a depth of 5mm and

dried at 50, 65 or 80°C. Results obtained indicated that a simple mass

transfer equation Ln [(C-C*)/(Co-C*)]=

-(K/L)t can be used to model the drying behaviour of the fermented milk -sorghum

flour mixtures. The

magnitude of mass transfer coefficient K, increased with drying temperature

and the germination of sorghum.

Germination and addition of milk increased the in vitro protein digestibility

of sorghum flour by 19.03%,

protein solubility by 11.5% and available lysine content by an average of 3.04%

and reduced the phytate

content by 30%. The water absorption capacity of flours was equally reduced

by an average of 4%.

Key words: Fermented milk, sorghum, malting, drying kinetic, physico-chemical

properties, nutritional properties.

INTRODUCTION

Fermentation is one of the oldest

methods of producing and preserving

foods. In Africa, this technology plays a

very important role in the nutrition and

daily diets of many populations.. The

common characteristics of such

fermentation is the production of

organic acids resulting in a reduction of

the pH and a typical sour taste. Besides

the beneficial effects of shelf life

extension and improvement of sensory

properties, it has been shown that certain

fermented milk based products have a

therapeutic effect in diarrhoea disease

(Boudraa et al.,1989).

Fermentation and germination are two

classical technologies commonly used to

improve on the protein digestibility and

the B6 vitamin content of cereals, either

by decreasing the amount of inhibitors

or releasing the nutrients for absorption

(Dhankher and Chauhan, 1987a;

Dhankher and Chauhan,1987b). By

using a lactic fermentation technique

combined with flour of germinated

seeds, the energy density in cereal based

gruel is significantly increased (Svanberg

and Sandberg, 1989), while at the same time bulk density is reduced (Mosha, and

Svanberg, 1990; Marero,et al., 1988).

Germination of cereals has equally been

found to increase the protein quality of

the malted flours apart from modifying

the starch granules (Opoku et al., 1983).

Germination studies have also shown

increase in vitamins and bioavailability

of traces minerals in the cereals sprouts.

In the central African region, and

especially in the northern parts of

Cameroon, cattle rearing and milk

production is the principal

preoccupation of the people. Excess milk

produced is often fermented and mixed

into a dough with cereal flour (maize,

sorghum, millet or rice) which is

subsequently cooked and consumed in

the form of gruel. This traditional

method of processing milk and cereals

permits the utilisation of excess milk and

contributes to ensure food security in

these areas. It certainly also improves

the protein-energy value of cereal based

diets. However the method is laborious,

very susceptible to bacterial

contamination and very likely to

influence the functional properties of

the flours obtained.

As part of main study aimed on

reducing the production time and

improving on the hygienic quality of this

milk-based cereal product, the present

study was carried out to determine the

effect of such production parameters

as germination and drying temperature

on the drying kinetic, the physicochemical

and nutritional properties of

the fermented milk-based-sorghum

flours.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Production of sorghum flours

A white cultivar of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), was obtained from the

experimental farm of the Institute for

Agronomic Research (IRAD) in Maroua,

Cameroon. Sorghum was cleaned and

soaked in distilled water (100 g in 300

ml) for 12 hours, rinsed and divided into

2 parts. One part was germinated in the

dark for 72 hours while the second part

was drained dry at ambient temperature

and dried in an oven at 50°C to a

constant weight. The germinated seeds

were equally drained and dried at 50°C.

The different sorghum samples were each milled into a fine flour (150µ)

using

a hammer mill. Flours obtained were

packaged in polyethylene bags and stored

in a fridge at 4°C until needed for use.

Fermentation of milk

Fresh milk was obtained from the

Canadian-run pilot dairy farm

(SOGELAIT) located close to the

University of Ngaoundere - Cameroon.

Pasteurised whole fresh milk was

aseptically inoculated with a dried starter

(Rhône - Poulenc, France) containing a

strain of Streptococcus thermophilus and one

strain of Lactobacillus bulgaricus, followed

by incubation for 3 hours at 40°C in a

thermostatically controlled water bath

and incubated for 3 hours at 40°C.

Production of milk-based sorghum

flours (MBSF)

MBSF were prepared by mixing

fermented milk and cereal flours in a

2:1 ratio (w/w) using a food mixer

(Kenwood, UK) to ensure proper mixing

and allowed to rest for 1 hr. The dough

obtained was spread uniformly on

aluminium plates of dimension 20 x 20

x 0.5 cm and dried to constant weight in

an air drought oven at 50, 65 or 80°C.

The drying process was monitored by

weighing the plates at regular intervals

using a Sartorius balance (sensitivity

0.001g). At the end of the drying

determined by a constant weight, the

dried dough was packaged in

polyethylene bags and stored in a

dessicator at 4°C until needed for use.

Analysis of chemical composition

of flours

MBSF were analysed for moisture,

proteins, ash and lipids essentially

according to standard AOAC methods

of the Association of Official Analytical

Chemists (AOAC, 1975). Flour samples

were acid-hydrolysed and the resulting

reducing sugar designated as available

carbohydrates, was determined by the

Dinitrosalisylic acid (DNS) method of

Fisher and Stein as described by

Fombang (1999). Phytates were

determined by the method described by

Thompson and Erdman (1982).

Analysis of functional properties

of flours

Water absorption capacity (WAC)

The evaluation of the rate of water

uptake of flour was carried out by the Baumann method as described by

Dumay et al. (1986). At least three

measurements were conducted for each

sample and the mean was expressed as

mL of liquid retained per gram of

sample.

Protein water solubility (PWS)

PWS of the MBSF was determined

essentially by the method of Oshodi and

Ekperigin (1989). A sample (0.02g) of

flour was added to 10 ml of distilled

water, mixed with a spatula and

centrifuged at 3500 rpm. The proteins

in the supernatant was determined by

the method of Lowry et al. (1951). The

solubility of proteins in water was

expressed as a percentage of the total

proteins.

Analysis of nutritional properties

of the milky flours.

In vitro protein digestibility was

determined by the method of Savoie

and Gauthier (1986). Following this

method, a sample containing about

450mg of protein was suspended in 17ml

of 0.1 N HCl and incubated in a shaking

water bath for 5 min. The pH was

adjusted to 1.9 and 2.5ml of 0.7%(w/

v) freshly prepared pepsin solution

(Sigma chemical Co, St Louis Mo) was

added, mixed and incubated at 37°C for

30 min. The reaction was stopped by

the addition of 1ml of 1N NaOH and

the volume adjusted to 23ml with

sodium phosphate buffer 0.1M, pH 8.

The lot was then transferred into a

dialysis tubing (Molecular weight cut off~ 1200, Medicell International Ltd,

London, U.K) following by the addition

of 2.5 ml of a phosphate buffer solution

containing pancreatine (0.7%w/v)

(Sigma chemical Co., St Louis Mo). The

tubing was then tied and introduced each

into a beaker containing 400ml of

phosphate buffer. The whole was

incubated at 37°C under agitation. At

regular time intervals, 2ml of dialysate

was withdrawn and the proteins

determined by the methods of Lowry

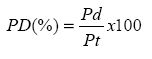

et al., (1951). The protein digestibility

(PD) at each time was calculated using

the formula:

Pd= protein in dialysate and Pt= total

protein in dialysis bag.

Available lysine was determined

according to the method of Kakade and

Liener (1969). Exactly 10.00 mg of

sample was mixed with 1ml of 4%

NaHCO3, pH 8.5 and incubated at 40°C

with agitation for 10min. This followed

by the addition of 1ml of 1% 2,4,6

trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)

further incubation for 2 hours at the end

of which 3ml of concentrated HCl was

added. The tubes were then autoclaved

at 120°C for 1 hr before cooling down

at room temperature. The contents of

the tubes were then diluted with 5 ml

of distilled water, filtered, washed twice

with 5ml of diethyl ether and placed in

boiling water to evaporate traces of

ether. The optical density of the solutions

were read at 346 nm against a blank

treated in the same manner but without

flour. The concentration of lysine was

calculated using the specific absorbance

of e-TNP lysine which is 14600Mcm-1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Drying behaviour of the flours

The drying curves of the different

MBSF are shown in figure 1. The initial

moisture content of the different milksorghum

mixtures of germinated and

non germinated sorghum were 60.08%

and 59.92 % respectively. Because of

the high level of the initial moisture

content, a constant rate period was

observed during the early parts of the

drying process. The falling rate period

appears directly after the constant rate phase. During this phase, it was assumed

that the resistance to mass transfer of

water vapour from the solid surface to

the air was negligible and the internal

resistance controlled the rate of drying

(Yener et al., 1987).

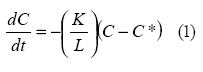

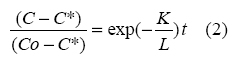

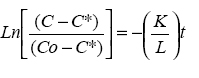

In this respect, an internal mass transfer

coefficient K was defined as

- Where K= mass transfer coefficient, m/

hr,

- L= Thickness of dried material, m,

- t= drying time

- C=Total moisture, kg moisture/kg dry

- solid,

- C*= Equilibrium moisture, kg moisture/kg dry solid

- Integration of equation (1) from Co to

C give

Equation (2) was rearranged as

and drying curves were drawn as Ln [(CC*)/(

Co-C*)] versus time (Figure 2).

Slopes of the curve from the beginning

of the falling period were determined

and used to calculate the values of K/

L. Dependence of K/L values on

temperature and germination of

sorghum is shown in table 1. This table

indicate that K/L increased with increase

in drying temperature (P<0.05) and

germination of sorghum grain (P<0.05).

This increase of K/L with germination

of sorghum might be due to the

hydrolysis of the starch and other

hygroscopic macromolecules which

reduce polar bonds capable of binding

to water molecules.

Chemical composition of the

flours

Sorghum flours:

Proximate composition of the sorghum

flours is shown in table 2. Germination

of cereals is known to influence its

phytate content (Larson and Sandberg,

1995). Germination led to a 30%

decrease in phytate content of sorghum.

This level of decrease in phytate is much

lower than that of 79% reported by

Larson and Sandberg (1995) for

germinated barley. The differences in

the rate of reduction obtained in this

study may be due to the difference in

phytase activity in both cereals or to the

different germination time.

The germination of sorghum also results

in a significant (P<0.05) fall in the

proximate composition of sorghum. In

this respect, a decreases in protein, fat

and carbohydrates content were in the

range of 9.9%, 20.8% and 8.2%

respectively. The decrease in fat content

during germination has been reported

by several authors (Kaukovirta et al.,

1993; Dibofori et al.,1994). A reduction

in carbohydrates following germination

has also been reported (Nout, 1991). The

decrease in content of macromolecules

during germination could be due to the

synthesis and activity of hydrolytic enzymes (lipases, proteases amylase).

Germination also led to a 7.67%

decrease in ash content of sorghum. This

decrease in ash content which represents

loss in minerals could be due to the

rootlet and to the washing of the grains

during germination.

Milky-based-sorghum flours

(MBSF)

Proximate composition of the different

MBSF is as shown in table 2. The

composition was not influenced by the

drying temperature. The addition of

fermented milk increased the protein

content in the blend by 43.84% and

45.32% for the flours with non

germinated sorghum and germinated

sorghum respectively. The reducing

sugar levels ranged from 37.7 to 38.9%

for non germinated and 32.4 to 33.6%

for geminated sorghum and reflected the

reducing sugar content of the sorghum

flour. As it would have been expected,

fermented milk also increased the ash

content by 5.17 to 7.24% respectively

for flours with germinated sorghum and

non germinated sorghum. This significant

(P<0.05) increase in ash is due to the

fact that milk is an important source of

such minerals as calcium and

phosphorus. The crude fat content

ranged from 7.61 to 7.83 for non germinated sorghum based flour and

from 7.02 to 7.25 for germinated

sorghum based flour.

Functional properties of the flours

Water absorption capacity and the

protein solubility are important

characteristics of flours because physicochemical

properties such as viscosity and

gelation are dependent on them (Cheftel

et al. 1977).

The initial water absorption rate (Vi)

(measured between 0 to 45 sec), the

maximum absorption capacity (Q) and

the water protein solubility (PWS) of the

milky flours are shown in table 3. Vi

and Q for the flours with non germinated

sorghum were higher than that for

germinated sorghum. Germination of

sorghum led to a reduction in the initial

rate of water absorption and also in the

maximum water absorption capacity.

Depending on drying temperature,

reduction in the initial rate of water

absorption varied between 36.55 and

42.05% while that of maximum water

absorption capacity varied between 2.84

and 4.7%.

On the other hand, germination led to

an increase in PWS with value ranging

from 10.58 to 12.86%. Drying beyond

65°C led to a reduction in PWS. For

flours dried at 80°C, protein solubility

decreased by 14.25 and 15.95% for non

germinated and germinated sorghum

respectively. The observed negative

effect of high drying temperature on the

solubility of proteins may be potentially

due to the formation of complexes

between soluble proteins and sugars such

as is often the case in Maillard reactions.

Nutritional characteristics

The incorporation of fermented milk

into sorghum flour significantly (P>0.05)

improved on its protein content.

Germination of sorghum further

improved on the protein in vitro

digestibility of the protein (Figure 3).

After 180 minutes of in vitro digestion,

flours made from fermented milk and

germinated sorghum showed a

digestibility rate of 23.51% as opposed to that of 19.75% observed for flours

containing non germinated sorghum.

Thus a significant improvement rate of

19.03% was attained in the digestibility

of the flours by germination of

sorghum. This increased rate may

partially be explained by the fact that

during germination, proteolytic enzymes

are synthesized which degrade proteins

to small water soluble peptides (Nout,

1991). Also it may be partially due to the fact that germination led to a felling

in phytate content which is known to

reduce protein digestibility (Poonam and

Sahl, 1994).

Depending on drying temperature, the

addition of milk increased the level of

available lysine in non germinated

sorghum from 18.25 to 40.52 mg/g of

protein while that in germinated

sorghum varied between 21.78 to 40.74

mg/g of protein on the average.

Germination of sorghum increases the

level of available lysine in flour. Increase

in available lysine levels following

germination has also been reported

(Dalby et al., 1976) for wheat. It is

established that during germination the

rate of synthesis of albumins and

glutamins which are proteins rich in lysine

decrease (Okkyung, and Yeshajahu,

1985).

Germination also led to a decrease of

the phytate content of sorghum flour.

In fact fermented milk-based-sorghum

flours are acidic, at this pH range,

proteins are generally charged positively

whereas phytates are negatively charged

(Reddy et al.,1982). As such, phytate

strongly bind protein particularly at their

e-NH2 group of lysine. This attraction

seemed to have been potentiated by high

drying temperatures, specially at 80°C

which a reduction of about 8.05 and

9.03% for germinated and non

germinated sorghum was observed.

CONCLUSION

On the whole, the results of this study

demonstrate the fact that use of

germinated sorghum and appropriate

drying temperature can greatly improve

the chemical and nutritional quality of

the fermented milk-based sorghum flour

commonly called Kindimu. Drying at

temperature below 65°C seem to be

preferable. Consumption of such foods

formulated from locally available food

stuffs may lead to the improvement of

the protein-energy status of the local

population. Several other types of

cereals (maize, sorghum, millet, rice) are

also traditionally used in the production

of these flours. In view of the fact that

these cereals differ in their characteristics

(chemical composition, physico-chemical

properties etc), it would be interesting

to exploit the other cereals for this same purpose to determine which is better

suited to the production of the milkbased

cereal flour.

REFERENCES

- AOAC., 1975. Official Methods of Analysis, 875-

876..Association of Official Analytical Chemists,

Washington.

- Boudraa, G.; Touhami, M.; Pochart, P.; Soltan,

R.; Mary, J.Y and J.F., 1989. Desjeux, Proc..

Congrès International sur Les Laits Fermentés:

Actualité de la recherche, pp. 229-232. Paris

.

- Cheftel, J.C; Cheftel, H and Besançon, P., 1977. Introduction à la biochimie et à la

technologie des aliments, Vol 2 420 pages, Tec. Doc. Lavoisier,

Paris.

- Dalby, A. and Tsai, C.Y. 1976. Lysine and

tryptophane increases during germination of

cereal grains. Cereal Chem., 53 :222-226.

- Dhankher, N. and Chauhan, B.M., 1987a.

Technical note: preparation, acceptability and Bvitamin

content of Rabadi- a fermented pearl

millet food.. Int. J. Food. Sci. Technol 22: 173-176.

- Dhankher, N. and Chauhan, B.M., 1987b. Effect

of temperature and fermentation time on phytic

acid and polyphenol content of Rabadi - a

fermented pearl millet food. J.Food.Sci 52: 489-

490.

- Dibofori, A.N; Okoli, P.N and Onigbinde; A.O.,

1994. Effect of germination on the cyanide and

oligosaccharide content of Lima bean (Phaseolus

linatus). Food chemistry. 51(2) : 133-136.

- Dumay, E.F.; Conder, F. and Cheftel, J.C., 1986. Préparations protéiques de graines de coton glandless: Caractérisation

des constituants

protéiques et propriétés fonctionnelles. Sci.

Aliments, 6: 623 -656.

- Fombang, N. E. , 1999. Studies on the effect

malting conditions on the level of some antinutrients

and nutrients in sorghum and bean

flours.. M.Sc thesis. University of Ngaoundere,

101 pages.

- Kakade, M.L. and Liener, I.E., 1969. Determination of Available

Lysine in Proteins. Analytical Biochemistry. 27: 273-280.

- Kaukovirta, N.A; Laakso, S.; Reinikainen, P.

and Olkku, J., 1993. Lipolytic and oxydative

changes of barley lipids during malting and

mashing. J. of the Institute of Brewing 99 (5): 395-

403.

- Larson, M. and Sandberg, A. S., 1995. Malting

of oats in pilot - plant process. Effects of heat

treatment and soaking conditions on phytate

reduction. J. Cereal Sci. 21 (1) : 87-95.

- Lowry, O.H., Rosebrough, N. J.; Farr, A.L.

and Randall, R. J., 1951. Protein measurement

with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chemistry,

193 265-269.

- Marero, L.M.; Payumo, E.M., Agninaldo, A.R.

and Homma, A., 1988. Technology of weaning

food fermentation prepared from germination

cereals and legumes. J. Food. Sc. 53 (3) 1391 - 1395.

- Mosha, A.C and Svanberg, U., 1990. Preparation

of weaning foods with high nutrient density using

flour of germinated cereals. Food and Nutrition

Bulletin, 12 69-74.

- Nout, M.J.R., 1991. Weaning foods for tropical

climates. Proc. Regional Workshop on Traditional

African Foods-Quality and Nutrition, pp 23-31.

Dar es Salaam.

- Okkyung, C. and Yeshajahu, P., 1985. Amino- acids in cereal

proteins and protein fractions. In: Digestibility and amino acid availability

in cereals

and oilseed Amino-acids in cereal proteins and

protein fractions. Ed. by Association of Cereals

Chemists, pp. 65-107. Minnosota.

- Opoku, A.R.; Osagie, A.U. and Ekpengin, E.R.,

1983. Changes in the major constituents of millet

(P.americanum) during germination. J. Agric. Food.

Chem. 37 507-509.

- Oshodi, A.A and Ekperigin, M.M.. 1989. Functional properties of

pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) flour. Food Chem. 34 187-191.

- Poonam, G. and Sahl, S., 1994. Protein and starch

digestibility and iron availability in developed

weaning foods as affected by roasting. J. of Human

Nutrition and Dietetics 7 121-126.

- Reddy, N.R.; Sathe, S.K., and Salunke, D.K.,

1982. Phytates in legumes and cereals. Adv. Food.

Res. 28: 1-92.

- Savoie, L. and Gauthier, F., 1986. Dialysis cell

for the in vitro measurement of protein. J. of Food

Sci. 51 (2) 494-498.

- Svanberg, U and Sandberg, A.S., 1989. Improved

iron availability in weaning foods using

germination and fermentation. In Nutrient

Availability: Chemical and Biological Aspects. Ed.

Southgate DAT, Johnson IT & Fenwick GR. Royal

Soc. Of Chem. Special publication 72: 179-181.

- Thompson, B.D. and Erdman, J.R.W. 1982. Phytic acid determination

in soy beans. J. of Food Sci. 47 513-516.

- Yener, E., Ungan, S. and Özilgen, M., 1987. Drying of Honey-Starch

Mixtures. J. of Food Sci. 52 (4) 1054-1058.

Copyright 2004 - The Journal of Food Technology in Africa, Nairobi

The following images related to this document are available:

Photo images

[ft04003t3.jpg]

[ft04003f2.jpg]

[ft04003f1.jpg]

[ft04003f3.jpg]

[ft04003t4.jpg]

[ft04003t2.jpg]

[ft04003t1.jpg]

|